As a well-known animation artist, Hayao Miyazaki (宮崎 駿) has established his political fables through his animated fictions for years. In 2003, Miyazaki acknowledged that he did not attend the Best Animated Feature Oscar ceremony for Spirited Away because he was disappointed in the US’s involvement in the Iraq War. As a self-proclaimed left-wing ideologist, Miyazaki has not only declared his rejection of violence but has also denounced the usage of nuclear power after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011. His angst of the future, mostly educational and

RESEARCH

environmental, has become a recurring theme in his narratives.

What makes Miyazaki’s art work distinctive to the Western viewers? Personally, I am inspired by the way he weaves animism into his stories. His fantasy worlds have always been filled with unknown spiritual power. Each object or each place has its own spirit or god inhabited within. Humans are not the dictatorial beings of the existing world, but they are instead living in symbiosis with the others. In addition, Miyazaki has portrayed many well-known multifaceted characters that don’t normally appear in animations, since they tend to cause confusion to children. Most of his antagonists grow with the protagonists as the stories unfold.

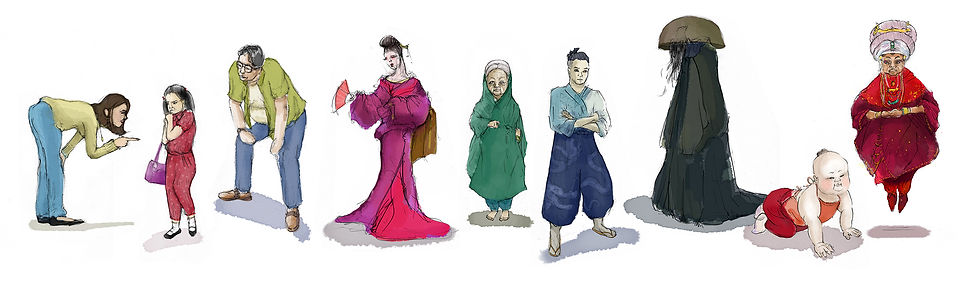

THE CHARACTERS

flicker immediately before all of the spirits arrive.

Furthermore, my research uncovered exiled artists who experienced similar warfare misfortune as Miyazaki, such as, Yasuo Kuniyoshi (国吉 康雄) and Léonard Tsuguharu Fujita (藤田 嗣治). I embed Middle-Eastern war monuments into the deserted landscape to resonate with the brutality of violence through the environment. The bright earthy tone of a desert contrasts with the dimmed and colorful spiritual world, which debuts later.

Since Spirited Away was created for the generation of the Lost Decade in Japan, I was intrigued by the socio-economic climate of the 90s. Japanese corporations outshined the international art market and purchased many iconic impressionist paintings before the economic bubble burst. Impressionism therefore became my first visual inspiration with which to begin the narrative—especially when Chihiro, the protagonist, crosses the boundary between the human and the spiritual world. She is clearly overwhelmed by the fleeting moments of light and color that

Designing the bathhouse in a circular compound structure is my response to its matriarchal totalitarian domain of the story. The bathhouse is ruled by Yubaba, a greedy witch who plays the main antagonist. I portray the bathhouse as a camp for reeducation, but it can also be viewed as a vibrant brothel—the epitome of a mature, urban metropolis .

THE BATHHOUSE

There are multiple air-docks designed for the flying spirits—the customers—on the upper levels of the main structure in order to emphasize the class system in a world of over-consumption.

STUDY MODEL

THE BOILER ROOM

1/4" Physical Concept Model

The boiler room is the key engine that keeps the bathhouse running. Kamaji is the sole spirit who runs the boiler and supervises its fuel system, and it provides purified heated water for the bathhouse. My rendition of the boiler room is built on an abandoned nuclear power plant. Imagine Kamaji: a mutated spirit who takes on the responsibility of purifying nuclear-contaminated water. He turns a simple-structured torii gate into a geothermal water cleansing control panel. His main goal is to fight against the nuclear waste leaking from a malfunctioning machine that was inspired by the Fukushima accident in 2011.

(A torii is a traditional Japanese gate most commonly found at the entrance of or within a Shinto shrine, where it symbolically marks the transition from the mundane to the sacred)